Darryl Tempero of Kiwi Church - A community of people strolling with God

BY DARRYL TEMPERO

This article first appeared in the July issue of Refresh - A Way Through The Valley: Contemplative gifts for the future of the church.

I remember a few years back sitting with Genesis 3, reading Eugene Peterson’s The Message translation, where he poetically describes the scenario in verse 8:

‘When they heard the sound of God strolling in the garden in the evening breeze…’

Strolling? The God I grew up with was walking. Walking is purposeful, it has a destination in mind with our eyes fixed looking ahead, and often is a task.

Strolling on the other hand is more relaxed, easy, with more potential to notice things around you. Most of all it is more intimate. When you stroll with someone you are more interested in the moment, rather than where you are going. You are more present to the person you are strolling with. It can also have a more contemplative feel to it.

It shifts how we think about church, our formation as community, and the role of contemplative prayer. I belong to a church we call Kiwi Church. It’s a network of small communities in Christchurch, and one in West Otago.

We talk about church as family who ‘strolls with God and each other.’

The essence of church is relationship, so we believe anything we do that nurtures the relationships between God and each other are valid expressions of church. This phrase of strolling with God captures the simplicity of how church can be. This has appealed to many of our people who’ve been part of church a long time, and have moved away from models of church that tend to have busy schedules and activities.

We want to explore more ‘being’ than ‘doing.’ We enjoy a number of ‘conversation partners’ who’ve strolled with us as we find our way – most significantly the Celts in the first millennium church. There are many aspects of their spirituality and Christian expression that resonate with us – and have much to teach us in 21st century Aotearoa.

These include: faith is embedded in the life of the Trinity; communities are organic and not overly structured; they are intentional about nurturing a healthy relationship with the land; and it’s natural to be able to find God in all things.

Most significantly is the monastic thread that weaves through their communities.

One of our companion partners is Simon Reed, author of Creating Community: Ancient Ways for Modern Churches – exploring what we learn about community from the Celts.

Simon set out to address two questions – essentially the same two Kiwi Church started with:

‘How do we create, maintain and deepen a genuine and lasting community,’ i

‘How do we create mature adult disciples of Jesus Christ?’ ii

This last question is critical because he found many people, including those who’d practiced Christian faith for many years, ‘didn’t feel a closeness or confidence in their relationship with God’ iii. This has also been our experience.

Tracey Balzer, another companion with us on the way, says the Celts ‘beckon us to join a life of freedom and joyful collaboration with God, where the holy presence of God himself can be easily accessed and enjoyed in particular places and experiences. Doesn’t that kind of life sound appealing?’iv It certainly does sound appealing to us, and maybe to many others in Aotearoa.

Reed, and others, taught us the Celtic Christian community was formed around three essential activities: a Way of Life, a network of Soul Friends, and a Rhythm of Prayer. In Kiwi Church, we focus on these, particularly exploring a Way of Life – akin to a monastic rule of life.

We adopted ‘Rhythm of Life’ because ‘rule’ tended to elicit unhelpful feelings from some who react to their church experiences from days gone by – we find the image of a trellis a helpful metaphor to help us grow.

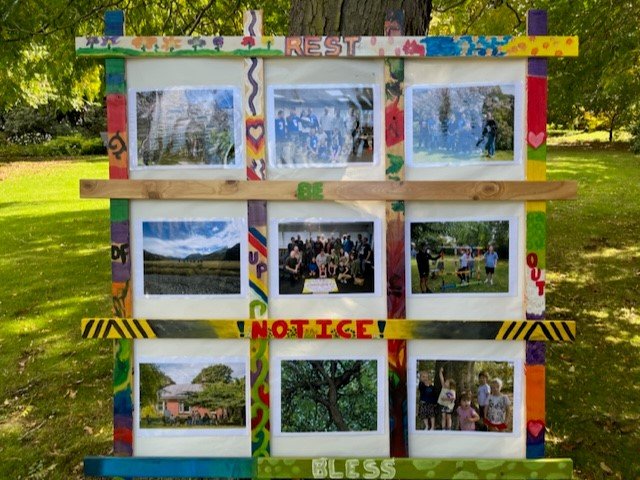

One Sunday we painted the wood to make up our trellis, and the next gathering the young people put it together. Our rhythm has four simple words [v]:

Rest Be Notice Bless

We want to take the Sabbath seriously and be more intentional with our rest. We want to ‘Be’ with God and commune with God. We want to notice what God is doing, and join in. We want to bless others – bless each other, our neighbour, the stranger, traveller, and our enemy.

These simple 4 words are finding a place in our lives. They resonate with their simplicity and depth – especially the ‘Be’ frame of the trellis.

The idea of moving from prayer as a ‘doing’ activity to a ‘being’ activity is now embraced by people in life giving ways, forming us as disciples, and helping nurture deeper relationships.

In our various gatherings we often practice of lectio divina, visio divina, Ignatian prayer, Centering Prayer, and silence. Our site has a stunning garden, so we enjoy gathering outside. It’s curious many people sense Gods closeness in the outdoors, yet most of usual church activities are inside – sometimes even looking at images of outside!

Our language is very intentional – ‘notice what you notice,’ ‘do what you can, not what you can’t’ and you are Gods ‘beloved.’ Henri Nouwen encouraged us to help each other live our lives hearing ‘you are beloved’ from the Father, and from one another.

Emotional health is important to us. In a world where powerful competing voices demand our attention, often in toxic ways which impact our well-being – this focus on the reality that we are God’s beloved helps to centre us. It allows us to be present to God in the midst of chaos. It is not easy, but it does bear fruit.

The place of contemplative prayer

Contemplative prayer is very different to the prayer our people have been used to. Many have found freedom in the mentoring of David Benner.

‘There is something seriously wrong when we feel like “prayer” something we should do.’ Prayer is more about invitation, ‘Simply saying yes to God’s invitation to a loving encounter.’

Ray Simpson helps us understand ‘contemplative prayer is natural, un-programmed; it’s perpetual openness to God, so in the openness God’s concerns can flow in and out of our minds as he wills.’vi

Contemplative prayer helps dismantle the secular/sacred split in which we express our faith and breaks down division between the activity of every-day life and prayer. Speaking of Celtic prayers Esther de Waal reminds us, ‘For the men and women who recited them, prayer was not a formal exercise: it was a state of mind.’vii

The word ‘invitation’ simply reframes our posture and activity as a church community. Many of our people have grown up with a frowning God, or a disappointed God. Over the years we identified unhelpful images of God (or as Joyce Huggett would say, the God of our guts’ viii ) and discover a God who smiles.

Dallas Willard says ‘Jesus only ever invites us to come to me, abide in me, learn from me, and follow me.’ Willard had a significant impact on me as a minister – responding to an invitation is way more attractive than doing something I think I should do. At Kiwi Church we try to encourage a posture of prayer that ‘punctuates the day and enables everyone consciously to connect with God and remember every hour belongs to him.’ix

There are echoes of Aotearoa’s indigenous spirituality with the Celts. Michael Mitton found, ‘With the Celtic love for creation, many connect with the seasons and with all the various aspects of life in God’s created order. Celtic Christians found it as natural to pray during the milking of a cow as they did to pray in church.

In fact, it is vital to feel at ease in praying while you are doing such mundane things as milking your cow, because, if you could not do that, your spiritual and earthly worlds were becoming far too separate. x

Encouraging contemplative practices have helped form us as individuals and as a community. They give permission for people to be authentic with God, help lighten a burden of expectation and sense of failure when it comes to prayer, and reframe it to be more accessible. We notice we become closer to each other when we spend time in contemplation together as it provides a delightful way to get to know each other more deeply. Plus it gives people a chance to take breath and time out from a busy, dusty world together.

Contemplating Scripture helps us engage with Gods word, moving from predominantly ‘reading and thinking,’ to more ‘listening and hearing.’ For some it has been freeing to ask: ‘what does it say?’ (as opposed to what does it mean?) It is a subtle but significant shift for those used to doing ‘quiet times’ and trying to ‘apply’ Scripture to their lives.

As well as the more familiar contemplative practices, whenever there is a 5th Sunday in the month we have ‘Outdoors church,’ where we go into the hills, by the sea, or in the bush, and spend time with God and each other.

Some gather regularly on a Saturday morning to create together – some paint, some knit, some take photos, all in a contemplative space which leads to taking delight in each other’s creativity – and to deepen relationships. We built a labyrinth in the garden and learned about it as an aid to prayer. We created a contemplative Easter journey to engage with the story more deeply.

Some comments from our people:

For the past two years, my experience of the Kiwi Church model and our emphasis on contemplative practice has been: simplification and growth, discovery and anticipation, greater experience of being on a shared journey with 'friends', greater trust of self and God's love of me, increased sense of relevance of faith to daily life and engagement in our complex world, fresh desire to be 'in step with God' on a daily basis. It’s liberating and lovely...and I'm just getting going ~ Dianne

Our practices together encouraged me to slow down and notice God in my day; Hearing what others have noticed in a contemplative space gives me another perspective. It helps me understand a bit more about their world and the sorts of things that are important to them. Shared contemplative experiences are about slowing down together, being with each other in the silence, being connected in a way that goes beyond words. ~ Ramon

Being (as opposed to doing), is particularly relevant to my personal/health and spiritual faith stages. My own mantra is to ‘not rush’ but enjoy what’s going on around me, so strolling along is a gift that Kiwi Church highlights. Strolling in silence; strolling, stopping & noticing; strolling with companions in conversation … often opportune and spiritually relevant, even if/when God is not mentioned. God is companion. Being outdoors allows creation to cushion our feet, feed our eyes and creates space to be creative, enter into God’s space, know presence at its/his most foundational. There’s family, there’s community … there’s finding soul friends. ~ Heather

At Kiwi Church we’re wanting to nurture an ecosystem in which contemplative practices play are vital part in our life together. We don’t do them to make anything ‘happen’, we do them because they help place us in the hands of our loving creator, who forms us into the people God made us to be.

They help us pause, take a breath, stroll with God, and notice the Divine’s loving gaze on us. It helps centre us, recalibrate us, and encourage us as we participate with God restoring all things.

I leave the final words to our friend Henri Nouwen:

‘Contemplative Prayer deepens in us the knowledge that we are already free, that we have already found a place to dwell, that we already belong to God, even though everything and everyone around us keep suggesting the opposite.’xi

Darryl Tempero is a follower of Jesus, a husband, father, minister, and lecturer who loves finding God in all things, including the outdoors, sport and movies.

[i] Simon Reed, Creating Community: Ancient Ways for Modern Churches (Abingdon, UK: BRF, 2013), Electronic Edition: Location 181.

[ii] Ibid., loc 200.

[iii] Ibid., loc 170.

[iv] Tracey Balzer, Thin Places: An Evangelical Journey into Celtic Spirituality (Abilene, TX: Leafwood Publishers, 2007), 32.

[v] Borrowed from our friend Rev Spanky Moore and the Vocatio community in Christchurch, although we use the word ‘Be’ rather than “Pray’ given our context of people who have some allergies to some church language.

[vi]Ibid.

[vii] Esther De Waal, The Celtic Way of Prayer: The Recovery of the Religious Imagination (Image, 1999), Kindle Electronic Edition: Location 950.

[viii] Joyce Huggett. Learning the Language of Prayer (Oxford, UK: The Bible Reading Fellowship, 1994) 91.

[ix] Reed, Creating Community, loc 323.

[x] Michael Mitton, Restoring the Woven Cord: Strands of Celtic Christianity for the Church Today 2nd ed. (Abingdon: BRF 2010), 3.

[xi] Henri Nouwen, In the Name of Jesus: Reflections on Christian Leadership (New York: Crossroad, 1993), 43.

This article first appeared in the July issue of Refresh - A Way Through The Valley: Contemplative gifts for the future of the church.

Refresh is SGM’s journal of contemplative spirituality in Aotearoa, New Zealand. You can view the current issue of Refresh or browse the archives in the Refresh section of this website.